Background: Osteocalcin (Oc) is the most abundant, non-collagen protein in bone and the 10th most abundant protein in the human body. Oc is a small protein, consisting of only 49 amino acids—but its most distinctive feature is the vitamin K-dependent gamma- (γ‑)carboxylation of up to three glutamic acid (Glu) amino acid residues—posttranslational modifications (PTMs) that add an extra side‑chain carboxylic acid group to Glu residues, converting them into “Gla” residues.

These modifications facilitate binding to calcium ions (Ca2+) and impart osteocalcin’s ability to influence bone mineralization via direct interaction with the hydroxyapatite bone mineral. A limited portion of circulating human osteocalcin possesses the full complement of three Gla residues; thus the relative abundance of human osteocalcin bearing 0, 1, 2, or 3 Gla residues varies depending on recent vitamin K status. Vitamin K in the diet comes primarily from vitamin K1 (a.k.a. phylloquinone), which (as part of the electron transport chain of Photosystem I) is mostly derived from leafy green vegetables.

Background: Osteocalcin (Oc) is the most abundant, non-collagen protein in bone and the 10th most abundant protein in the human body. Oc is a small protein, consisting of only 49 amino acids—but its most distinctive feature is the vitamin K-dependent gamma- (γ‑)carboxylation of up to three glutamic acid (Glu) amino acid residues—posttranslational modifications (PTMs) that add an extra side‑chain carboxylic acid group to Glu residues, converting them into “Gla” residues.

These modifications facilitate binding to calcium ions (Ca2+) and impart osteocalcin’s ability to influence bone mineralization via direct interaction with the hydroxyapatite bone mineral. A limited portion of circulating human osteocalcin possesses the full complement of three Gla residues; thus the relative abundance of human osteocalcin bearing 0, 1, 2, or 3 Gla residues varies depending on recent vitamin K status. Vitamin K in the diet comes primarily from vitamin K1 (a.k.a. phylloquinone), which (as part of the electron transport chain of Photosystem I) is mostly derived from leafy green vegetables.

Detailed Quantification of Osteocalcin's ModificationsClick Here for Our Paper

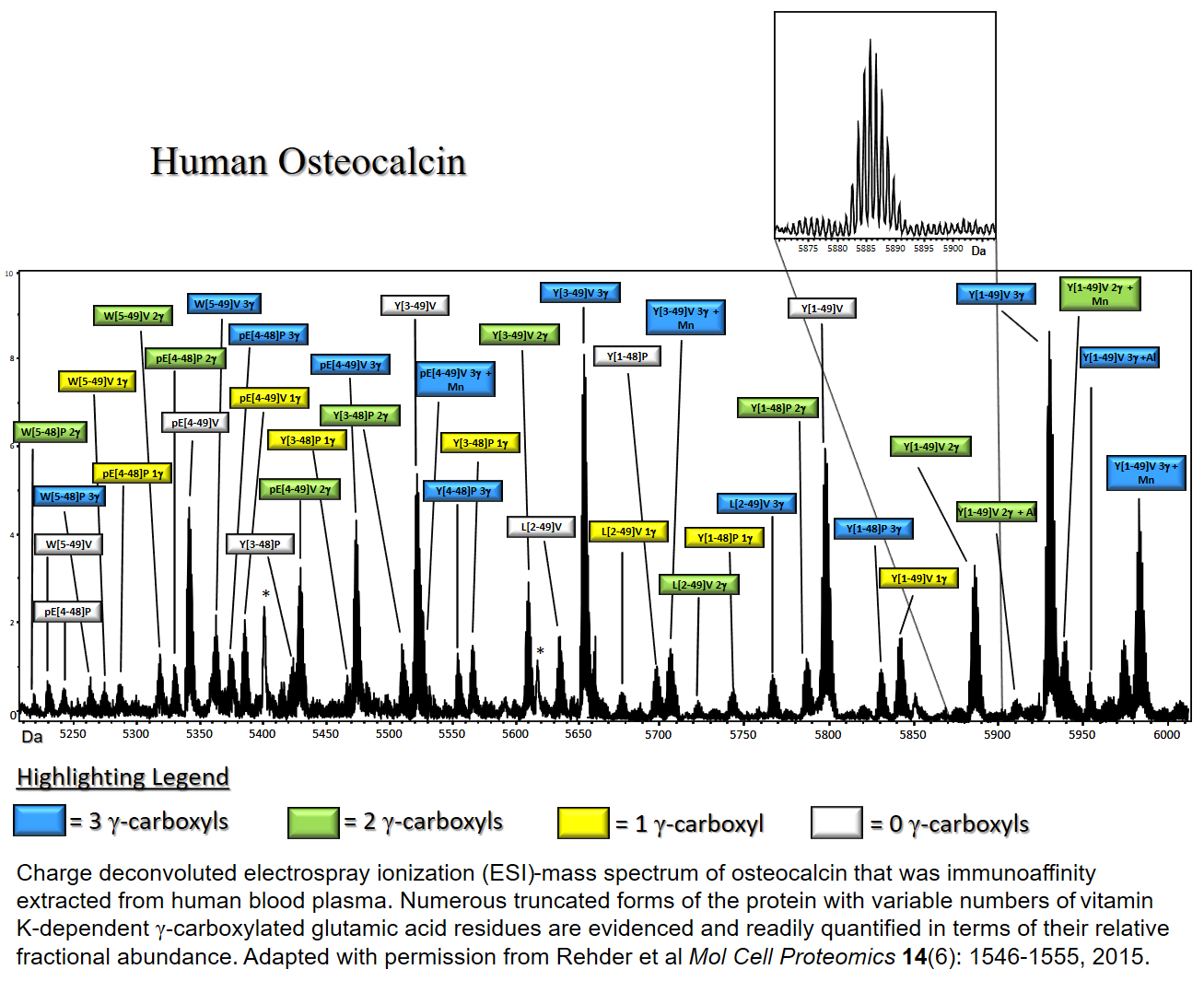

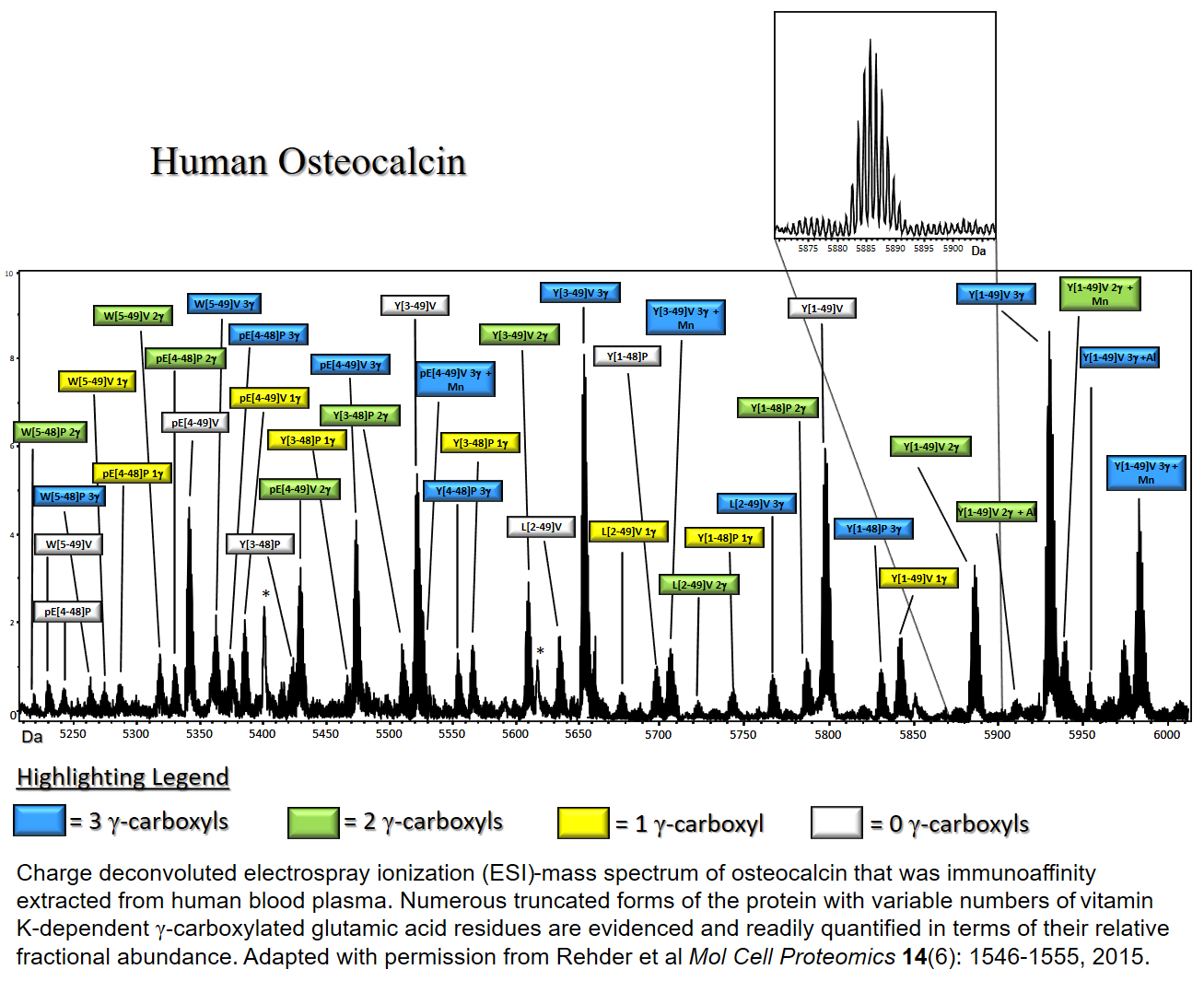

Clinically, circulating concentrations of osteocalcin are employed as a marker of bone formation and overall bone turnover. We have found that osteocalcin circulates in over 20 differentially truncated forms. Each one of these forms can be modified by 0,1,2 or 3 vitamin K‑dependent γ‑carboxyl groups which affect the ability of osteocalcin to bind calcium (as well as other metals). Existing clinical assays are blind to these modifications. The assay that we have developed gives researchers the ability to study the function of osteocalcin in ways that have previously not been possible. As such, it promises to provide new insights into its biological function. An annotated example of the charge‑deconvoluted mass spectral output from the assay is shown in the figure in this panel.

Clinically, circulating concentrations of osteocalcin are employed as a marker of bone formation and overall bone turnover. We have found that osteocalcin circulates in over 20 differentially truncated forms. Each one of these forms can be modified by 0, 1, 2 or 3 vitamin K‑dependent γ‑carboxyl groups which affect the ability of osteocalcin to bind calcium (as well as other metals). Existing clinical assays are blind to these modifications. The assay that we have developed gives researchers the ability to study the function of osteocalcin in ways that have previously not been possible. As such, it promises to provide new insights into its biological function. An annotated example of the charge‑deconvoluted mass spectral output from the assay is shown in the figure in this panel.

Clinically, circulating concentrations of osteocalcin are employed as a marker of bone formation and overall bone turnover. We have found that osteocalcin circulates in over 20 differentially truncated forms. Each one of these forms can be modified by 0, 1, 2 or 3 vitamin K‑dependent γ‑carboxyl groups which affect the ability of osteocalcin to bind calcium (as well as other metals). Existing clinical assays are blind to these modifications. The assay that we have developed gives researchers the ability to study the function of osteocalcin in ways that have previously not been possible. As such, it promises to provide new insights into its biological function. An annotated example of the charge‑deconvoluted mass spectral output from the assay is shown in the figure in this panel.

Application of the AssayClick Here for Our Paper

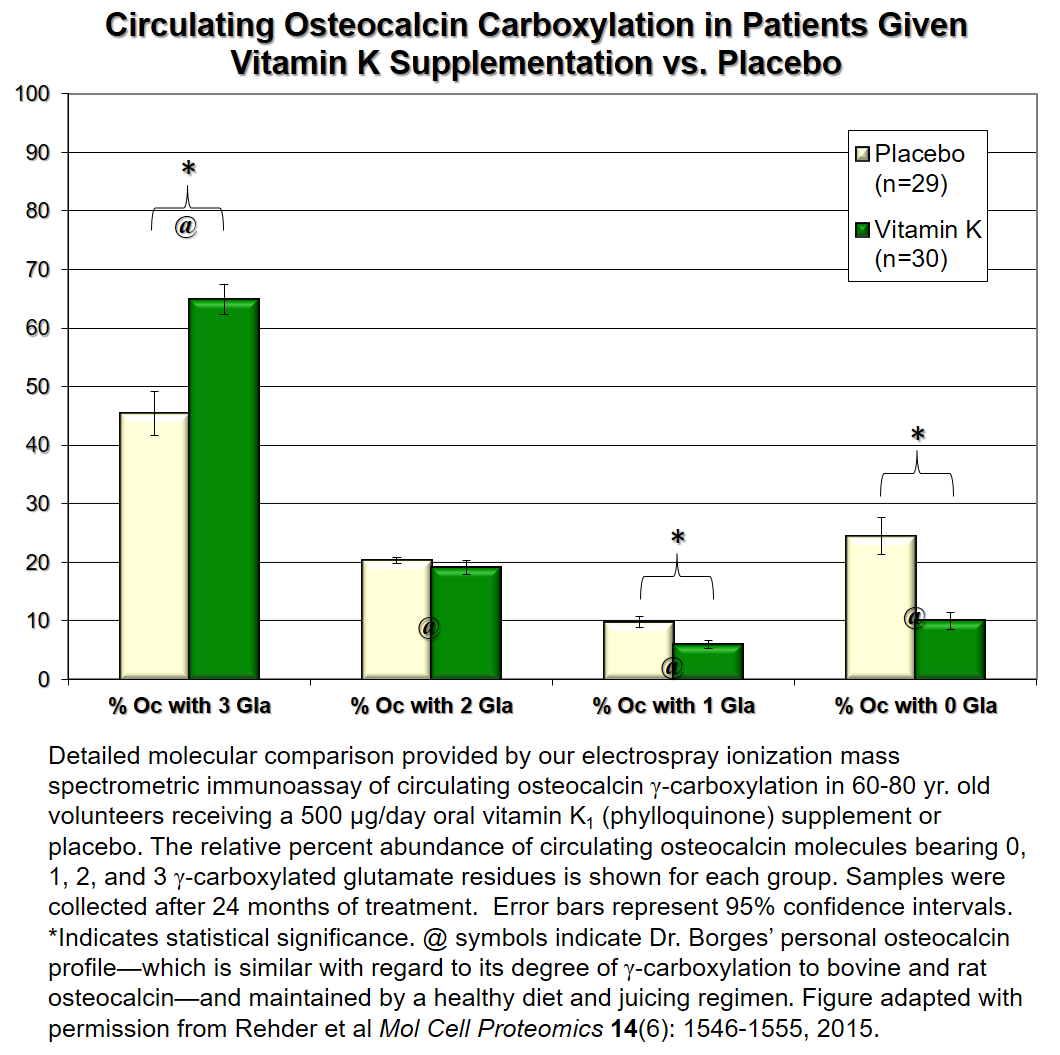

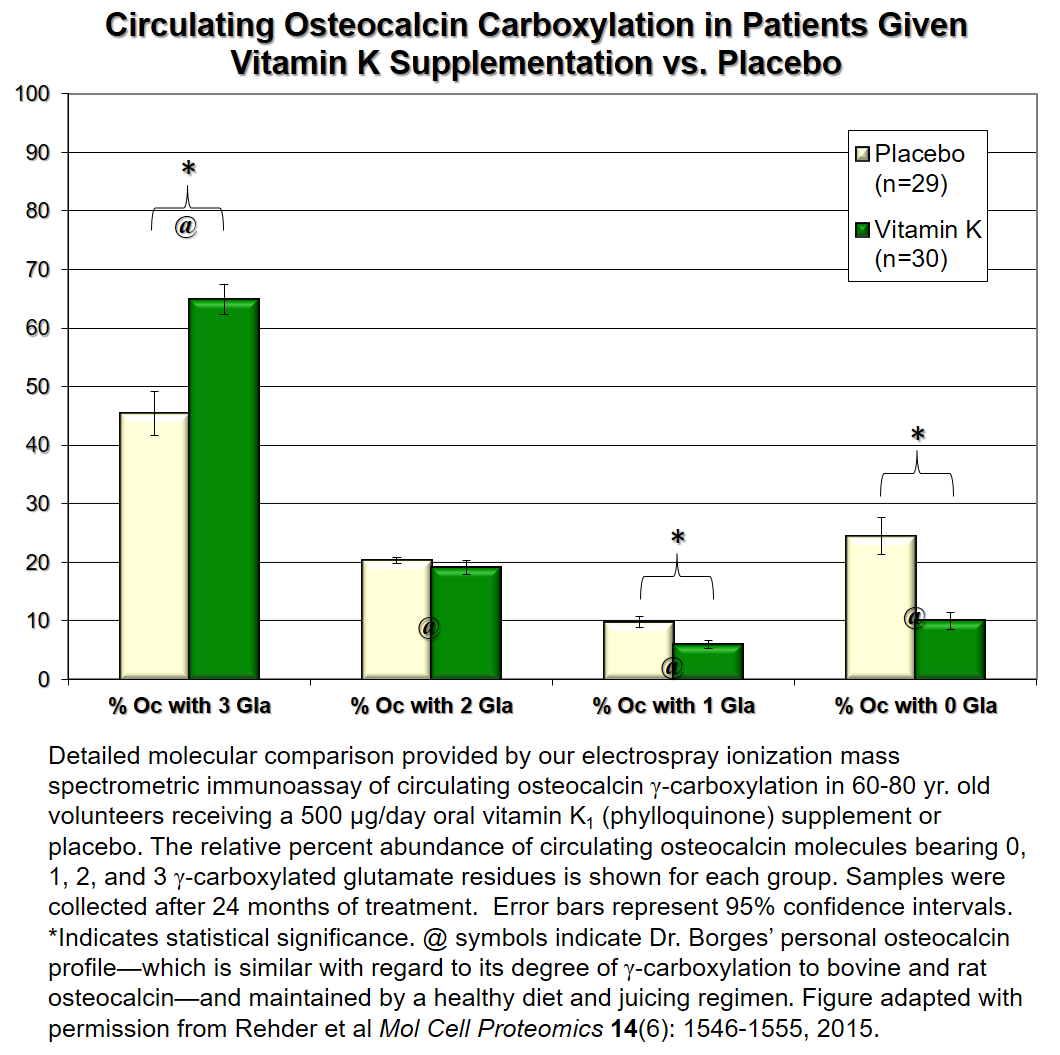

After developing the assay, we used it to quantify the precise fractions of circulating osteocalcin protein bearing 0, 1, 2, or 3 γ‑carboxylated glutamate residues in a double-blind controlled trial of nominally healthy 60-80 year olds maintained on their normal diet or supplemented with 500 micrograms of vitamin K1 (phylloquinone) per day. Results (shown the figure below), reveal that most older Americans on a typical diet consume inadequate quantities of vitamin K (which is found primarily in green leafy vegetables) to fully γ‑carboxylate their osteocalcin (yellow bars). This can be improved with vitamin K supplements (green bars). Interestingly about 80% of cow, rat and mouse osteocalcin bears 3 γ‑carboxyl groups—suggesting that humans (older Americans at least) tend to be vitamin K deficient—even though adequate vitamin K is consumed to maintain proper blood coagulation processes. The health consequences of maintaining such vitamin K levels are currently unknown, but may, according to NIH-funded vitamin K experts, have a role to play in Alzheimer’s Disease.

After developing the assay, we used it to quantify the precise fractions of circulating osteocalcin protein bearing 0, 1, 2, or 3 γ‑carboxylated glutamate residues in a double-blind controlled trial of nominally healthy 60-80 year olds maintained on their normal diet or supplemented with 500 micrograms of vitamin K1 (phylloquinone) per day. Results (shown the figure in this panel), reveal that most older Americans on a typical diet consume inadequate quantities of vitamin K (which is found primarily in green leafy vegetables) to fully γ‑carboxylate their osteocalcin (yellow bars). This can be improved with vitamin K supplements (green bars). Interestingly about 80% of cow, rat and mouse osteocalcin bears 3 γ‑carboxyl groups—suggesting that humans (older Americans at least) tend to be vitamin K deficient—even though adequate vitamin K is consumed to maintain proper blood coagulation processes. The health consequences of maintaining such vitamin K levels are currently unknown, but may, according to NIH-funded vitamin K experts, have a role to play in Alzheimer’s Disease.

After developing the assay, we used it to quantify the precise fractions of circulating osteocalcin protein bearing 0, 1, 2, or 3 γ‑carboxylated glutamate residues in a double-blind controlled trial of nominally healthy 60-80 year olds maintained on their normal diet or supplemented with 500 micrograms of vitamin K1 (phylloquinone) per day. Results (shown the figure in this panel), reveal that most older Americans on a typical diet consume inadequate quantities of vitamin K (which is found primarily in green leafy vegetables) to fully γ‑carboxylate their osteocalcin (yellow bars). This can be improved with vitamin K supplements (green bars). Interestingly about 80% of cow, rat and mouse osteocalcin bears 3 γ‑carboxyl groups—suggesting that humans (older Americans at least) tend to be vitamin K deficient—even though adequate vitamin K is consumed to maintain proper blood coagulation processes. The health consequences of maintaining such vitamin K levels are currently unknown, but may, according to NIH-funded vitamin K experts, have a role to play in Alzheimer’s Disease.

Clinically, circulating concentrations of osteocalcin are employed as a marker of bone formation and overall bone turnover. We have found that osteocalcin circulates in over 20 differentially truncated forms. Each one of these forms can be modified by 0, 1, 2 or 3 vitamin K‑dependent γ‑carboxyl groups which affect the ability of osteocalcin to bind calcium (as well as other metals). Existing clinical assays are blind to these modifications. The assay that we have developed gives researchers the ability to study the function of osteocalcin in ways that have previously not been possible. As such, it promises to provide new insights into its biological function. An annotated example of the charge‑deconvoluted mass spectral output from the assay is shown in the figure in this panel.